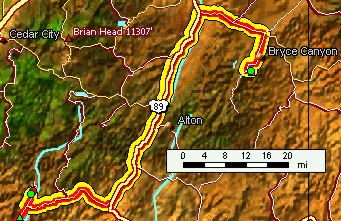

East Zion - Bryce

Reluctantly we left Zion Canyon, but with hopes for more great things ahead. Just past the Zion-Mt. Carmel tunnel, we stopped for a brief goodbye to Zion's spectacle along the Pine Creek trail.

East Zion - Bryce

Reluctantly we left Zion Canyon, but with hopes for more great things ahead. Just past the Zion-Mt. Carmel tunnel, we stopped for a brief goodbye to Zion's spectacle along the Pine Creek trail. |

|

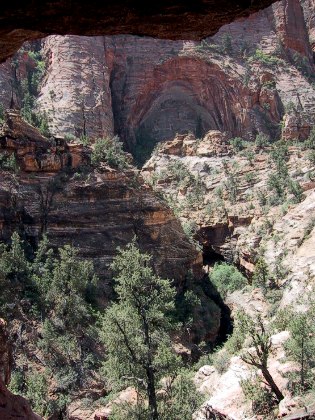

wall arch and slot canyon |

This is supposed to be a strenuous trail, but even with legs still humming from the day before's exertions, it seemed like a walk in the park. From a cave caused by a line seep, the view across the narrow canyon demonstrated the forces that formed Zion.

flowers along the trail |

Along the trail, the first place many visitors encounter, we chatted with a lovely British fellow who said he thought our National Parks were wizard. We replied that we liked his National Trust. "Ah, yes, but..." he said, sweeping his hand across the panorama before us. Unanswerable. |

East Temple from Pine Creek trail |

into Zion Canyon from Pine Creek overlook | |

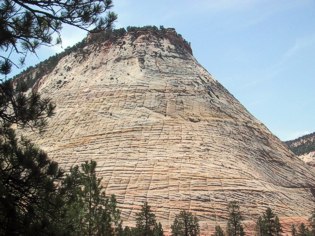

Checkerboard Mesa |

The road winds along Clear Creek, a beautiful miniature version of Zion, then rounds the base of Checkerboard Mesa, a magnificent pile of cross-bedded white Temple Cap limestone criss-crossed with erosion lines that take advantage of the weaker stone. |

Bryce Canyon National Park

We arrived at Bryce with plenty of time for a lunch on a bench overlooking the Queen's Garden and to make the scenic drive before checking in at the Lodge.

Hoodoos from Rainbow Point |

Queen's Garden from Sunrise Point |

Hoodoos |

Bryce's soft, brightly colored sandstone is made for technicolor shots, and the high-altitude blue sky, photogenically sprinkled with poofy white clouds, makes for pretty pictures. Somehow, this didn't seem too inviting to us after Zion's immediacy and liveliness.

What, exactly, are the ingredients that led us to enjoy Zion so much, and find Bryce cold and unapproachable? Water, certainly, and being amongst the monuments looking up, not on the rim looking down. We found the folks at Zion more approachable and warm -- could they be feeling the same? |

Improbable formation at Ponderosa Canyon overlook

Bryce sits at almost 9,000 feet elevation atop the stack of strata that make up Utah's "Color Country", and we found ourselves to be headachey and nauseous -- classic altitude sickness, for which the only cure is going down the mountain, and so very early the next morning that's exactly what we did, without the slightest sense of loss. |

Natural Arch |

Kanab Country

Kanab is an unprepossessing town that many tourists use as their base of operations for "Color Country." Conscious of the fact that tourism is its most important product, Kanab musters plenty of good food and small attractions. It's just below 5,000 feet, and so we were grateful for the chance to acclimate in comfort. |

|

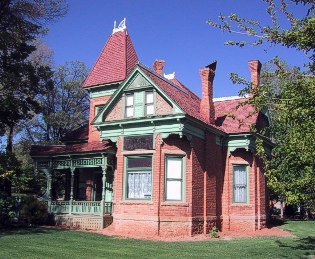

Heritage House |

Kanab's roots go back to Brigham Young's southwestern empire, as this fine old brick house proves. Built between 1892 and 1894, it's a fine time machine for taking us back a century to see how folks lived in this desert place. Its bricks, shingles, and ponderosa pine timbers came from nearby, but its glass, hardwood trim, woodstove, and crockery came the hard way, by wagon from the east. |

Some of the house's parts and fittings are of uncertain origin, and its keepers, well-intentioned Kanab elders whose grandparents were alive at the time of its building, don't know how all the parts came together. What is known is that the house was built for the Bowmans, but when Elder Bowman was called on a mission, it was taken over by the Chamberlain family, and used as their community center.

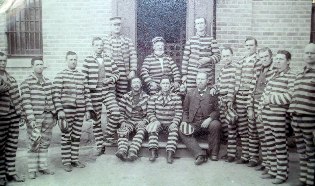

For the Chamberlains were a community unto themselves, and sufficiently numerous to comprise a good share of their greater community. With his six wives, Chamberlain managed to reproduce himself in the best Mormon pioneer fashion. |

Redwood pipe from Caspar? |

the Chamberlain girls |

the Chamberlain boys |

Chamberlain (left of door, in back)

Chamberlain did time for his beliefs, as the US Government forced the State of Utah to impose the prevailing prejudice against polygamy. Our guide was herself the daughter of a polygamous family, and was quick to say "while we don't practice this today," but could see no fault in it.

Chamberlain's wives didn't all live in this house. Some maintained their own homes as far away as Orderville, a days ride north. But when there were events in town, and for the children here for schooling, this house was the center.

Heritage House kitchen

|

Seeing how these folks lived, it's really not difficult to understand the sense behind plural marriage: there were fewer men, as their work was dangerous, and the most dangerous work a woman did was childbearing, so if many children was the goal, as it must be on a frontier...

It's good to see that the latter day Utahans can have a little fun with this legacy -- and let it be noted that food and drink here in Kanab is cosmopolitan and delicious -- life in Kanab and the Arizona Strip -- the section between the Cliffs and the Grand Canyon -- was rugged. The downstairs is wall-papered and outfitted with amenities, but the upstairs was never plastered over the laths, and there were (and still are) holes one could throw a cat through between wall and roof and between roof planes. The girls living upstairs had to chip through the ice on their basin before their morning ablutions, because winters in the high desert are as bitterly cold as the summers are brutally hot. |

This was a thrifty, waste-not, want-not life. This rolling pin has a story: When in the course of wagonning west, the going got tough and the axles wore out, it sometimes became necessary to lighten the load. The old kitchen table was heavy, but the legs were stout and well-turned, and so one at least was salvaged and recycled into further kitchen service, and could serve today.

Deseret Telegraph at Pipe Spring |

table-leg rolling pin

Life was hard, but it wasn't isolated. As the railroads met near Salt Lake City, and the continental telegraph with them, Brigham Young carried the technology on, building a telegraph line through St George, his southern capital, and across the Arizona Strip past Pipe Spring to Kanab. |

On a bright, cool day, we visited another early Mormon homestead, a fortified home of great simplicity, at Pipe Spring, a bit of rare water on the desert Strip. Mormon families often tithed in kind, and these cattle ("kind" being old English for cattle) were driven out to this station on halfway between Kanab and Hurricane. Pipe Spring -- the Spring is beneath the parlor floor, within the stockade -- was also a repeater station for the Deseret Telegraph. Now, it's an out-of-the-way National Monument. |

Winsor Castle at Pipe Spring |

Why fortified? Because the local natives weren't reliably peaceful when it came to taking their sparse water sources. The only "attack" ever fended off here was from Utah marshals making polygamy sweeps (and that explains the observation tower) but when the "castle" at Pipe Spring -- really nothing more than a four room "big house" with bunkhouses outside the walls, that typically served two dozen or more Mormon cowpokes as well as the manager and his family -- there were still hostilities and posturing going on between whites, the peaceful local Paiutes, and angry bands of dispossessed Apaches, Utes, and others. By 1880, with the signing of the eighth Indian peace treaty, things had calmed down, but memories of massacres on both sides were fresh.

The cattle station served for barely more than a decade, because the native bunch grass that originally made the Strip look like a rolling, fertile pasture, turned out to be unable to sustain the ravages of grazing. In less than twenty years, the Strip was turned into arid high desert, and remains that way a century later. This story, so often repeated west of the Hundredth Meridian, is the tragedy of the West.

|

Devil's Claw cactus in bloom

Water from Pipe Spring, on the Sevier Fault, still trickles out, but barely sustains a very few head of longhorn and the Station's oasis. The bunch grass has still not regenerated; it may have been a remnant of milder times.

|

The tragedy is aggravated now by the drought which has afflicted the Southwest for four years, and so even the desert is drying up and dying. Many cacti bloom as best they can when stressed, but the resources are stretched beyond blooming for many. The Beavertail cacti are wrinkled and dying.

Beavertail Cactus and Piñon stump

John Wesley Powell, one-armed first explorer of these parts, predicted that using the land would kill it ...and so untold investment of human energy and suffering quietly moulders here, in gentle testimonial to how little we know. |

This same windy dry day we stopped by Coral Pink Sand Dunes, an unexpected repository for every bit of Navajo sandstone of a particular size -- the wind is a choosy collector -- ever chipped off a neighboring cliff or hoodoo. Millennia in the building, we were glad to find it quiet and stately, even if the ATV's attack on weekends... |

Coral Pink Sand Dunes |

Heart rates and heads restored by lower altitude, good food, and a couple of episodes of our favorite TV shows, we packed up and headed back up the mountain, southward this time, to the Kaibab Plateau, and the northern edge of the Grand Canyon.

|

|

|

updated 21 May 2002 : 14:44 Caspar (Pacific) time this site generated with 100% recycled electrons! send website feedback to the Solarnet webster |

© 2001-2002 by Caspar Institute. All Rights Reserved. | |